Definitions: Systems, Systems Theory, Systems Thinking, Tools

What's a System?

Adapted from the Field Guide to Consulting and Organizational Development: Collaborative and Systems Approach to Performance Change and Learning.

One of the biggest breakthroughs in how we understand and guide change in organizations is systems theory and systems thinking. To understand how they are used in organizations, we first must understand a system. Many of us have an intuitive understanding of the term. However, we need to make the understanding explicit in order to use systems thinking and systems tools in organizations.

Simply put, a system is an organized collection of parts (or subsystems) that are highly integrated to accomplish an overall goal. The system has various inputs, which go through certain processes to produce certain outputs, which together, accomplish the overall desired goal for the system. So a system is usually made up of many smaller systems, or subsystems. For example, an organization is made up of many administrative and management functions, products, services, groups and individuals. If one part of the system is changed, the nature of the overall system is often changed, as well -- by definition then, the system is systemic, meaning relating to, or affecting, the entire system. (This is not to be confused with systematic, which can mean merely that something is methodological. Thus, methodological thinking -- systematic thinking -- does not necessarily mean systems thinking.)

Systems range from simple to complex. There are numerous types of systems. For example, there are biological systems (for example, the heart), mechanical systems (for example, a thermostat), human/mechanical systems (for example, riding a bicycle), ecological systems (for example, predator/prey) and social systems (for example, groups, supply and demand and also friendship). Complex systems, such as social systems, are comprised of numerous subsystems, as well. These subsystems are arranged in hierarchies, and integrated to accomplish the overall goal of the overall system. Each subsystem has its own boundaries of sorts, and includes various inputs, processes, outputs and outcomes geared to accomplish an overall goal for the subsystem. Complex systems usually interact with their environments and are, thus, open systems.

A high-functioning system continually exchanges feedback among its various parts to ensure that they remain closely aligned and focused on achieving the goal of the system. If any of the parts or activities in the system seems weakened or misaligned, the system makes necessary adjustments to more effectively achieve its goals.

A pile of sand is not a system. If you remove a sand particle, you have still got a pile of sand. However, a functioning car is a system. Remove the carburetor and you no longer have a working car.

System Theory

History and Orientation

Hegel developed in the 19th century a theory to explain historical development as a dynamic process. Marx and Darwin used this theory in their work. System theory (as we know it) was used by L. von Bertalanffy, a biologist, as the basis for the field of study known as ‘general system theory’, a multidisciplinary field (1968). Some influences from the contingency approach can be found in system theory.

Core Assumptions and Statements

System theory is the transdisciplinary study of the abstract organization of phenomena, independent of their substance, type, or spatial or temporal scale of existence. It investigates both the principles common to all complex entities, and the (usually mathematical) models which can be used to describe them. A system can be said to consist of four things.

- The first is objects – the parts, elements, or variables within the system. These may be physical or abstract or both, depending on the nature of the system.

- Second, a system consists of attributes – the qualities or properties of the system and its objects.

- Third, a system had internal relationships among its objects.

- Fourth, systems exist in an environment.

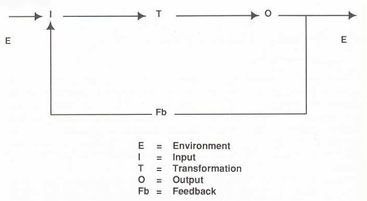

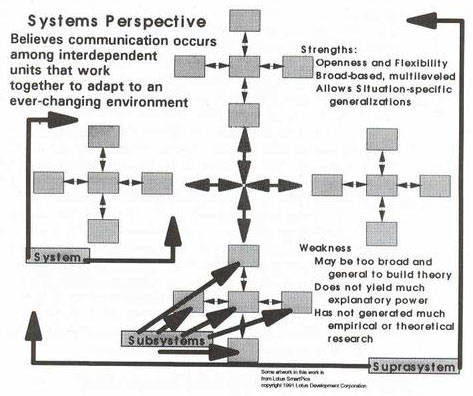

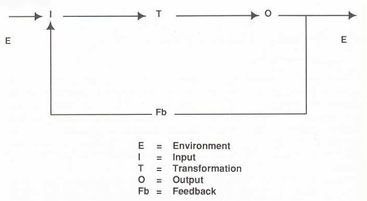

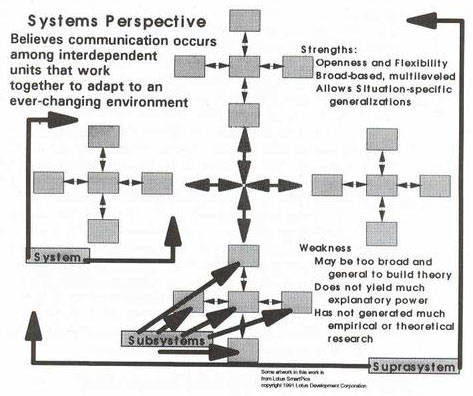

A system, then, is a set of things that affect one another within an environment and form a larger pattern that is different from any of the parts. The fundamental systems-interactive paradigm of organizational analysis features the continual stages of input, throughput (processing), and output, which demonstrate the concept of openness/closedness. A closed system does not interact with its environment. It does not take in information and therefore is likely to atrophy, that is to vanish. An open system receives information, which it uses to interact dynamically with its environment. Openness increases its likelihood to survive and prosper. Several system characteristics are: wholeness and interdependence (the whole is more than the sum of all parts), correlations, perceiving causes, chain of influence, hierarchy, suprasystems and subsystems, self-regulation and control, goal-oriented, interchange with the environment, inputs/outputs, the need for balance/homeostasis, change and adaptability (morphogenesis) and equifinality: there are various ways to achieve goals. Different types of networks are: line, commune, hierarchy and dictator networks. Communication in this perspective can be seen as an integrated process – not as an isolated event.

Conceptual Model

Simple System Model.

Source: Littlejohn (1999)

Elaborated system perspective model.

Source: Infante (1997)

Favourite Methods

Network analysis, ECCO analysis. ECCO, Episodic Communication Channels in Organization, analysis is a form of a data collection log-sheet. This method is specially designed to analyze and map communication networks and measure rates of flow, distortion of messages, and redundancy. The ECCO is used to monitor the progress of a specific piece of information through the organization.

Scope and Application

Related fields of system theory are information theory and cybernetics. This group of theories can help us understand a wide variety of physical, biological, social and behavioral processes, including communication (Infante, 1997).

Example

Take for example family relations.

References

Key publications

Bertalanffy, von, L. (1968). General systems theory. New York: Braziller.

Laarmans, R. (1999). Communicatie zonder Mensen. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Boom.

Luhmann, N. (1984). Soziale Systeme. Grund einer allgemeinen Theorie. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Midgley, G. (Ed.) (2003). Systems thinking. London: Sage.

Littlejohn, S.W. (2001). Theories of Human Communication. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/ Thomson Learning.

Infante, D.A., Rancer, A.S. & Womack, D.F. (1997). Building communication theory. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press.